We know that regular exercise boosts our health because we’ve been told this by virtually everyone since we were born. But how does physical activity do that exactly? Better understanding of intuitive truths helps us better regulate our own emotions towards exercise and manage it better so it seamlessly integrates in our life.

Before we even deal with the many benefits of exercise we need to briefly explore the exercise paradox: From an evolutionary perspective we evolved to avoid exercise despite the fact that in order to remain mentally, physically and psychologically healthy we need to be physically active.[1] The reason for that is found in the way our body evolved over hundreds thousands of years to adapt to a hostile environment.

To survive we need energy. From an evolutionary perspective we evolved to adapt quickly to our potentially hostile and physically demanding environment. The adaptations we experience from physical activity: bigger, stronger muscles, increased aerobic capacity and endurance also cost energy. The body then won’t trigger these adaptations unless it is convinced we need them. This is one reason why, when we exercise today, we don’t immediately see the benefits. Once they have been triggered, the moment the body feels we don’t need those bigger, costlier muscles or expanded lung capacity, it drops them. That’s also why the moment we stop exercising we experience a drastic drop in fitness level.

The body’s obsessive focus on energy costs is also the reason why we also like sitting around and doing nothing. Our ancient bodies don’t know that when we are ‘active’ in our daily life we use machines to get around and mostly work sitting down. Because our body doesn’t really know or understand that it tries to get us to rest when we have nothing physically demanding to do.

Whenever we do something that is really good for us we get a sense of wellbeing because dopamine levels increase and that drives part of our motivation to do things. We all know the feeling we get after vigorous exercise when we feel tired but happy and sort of vibrant inside. The thing is that while we are sitting down doing nothing the dopamine released is intended to make us continue to sit down and do nothing. To break that neurochemical hold on us and to switch it to physical activity we need to have a carefully worked out routine and an environment that helps us do it.

If, for instance, in order for us to exercise we need to find shoes, clothes, arrange for someone to watch the kids and then drive somewhere special for us to workout or have to somehow find a special place then it is unlikely that we will actually manage it and even if we do it is unlikely that we will stick to it. The obstacles are just too many.

Once we do manage, however, to make exercise something we do every day the benefits we get exceed what we normally think which is weight control, greater strength, endurance and more energy.

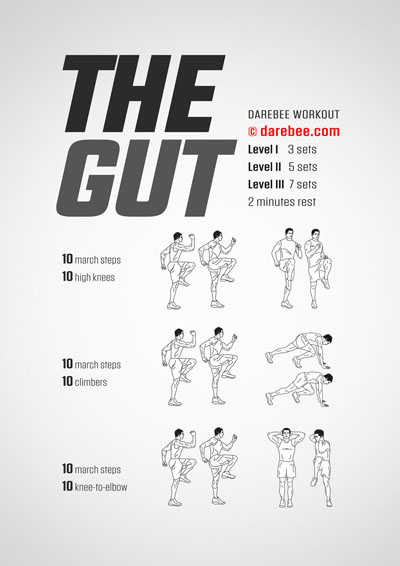

Reconfigure Your Gut Bacteria

Your gut bacteria or microbiome are responsible for immune system health, cognitive health and the way hormones are produced by the body and affect everything from mood to motivation.

Two new studies[2] have produced conclusive evidence[3] that shows that regular exercise can reconfigure the gut microbiome and change the signature of the hormonal signals that run many of our physical and cognitive functions.

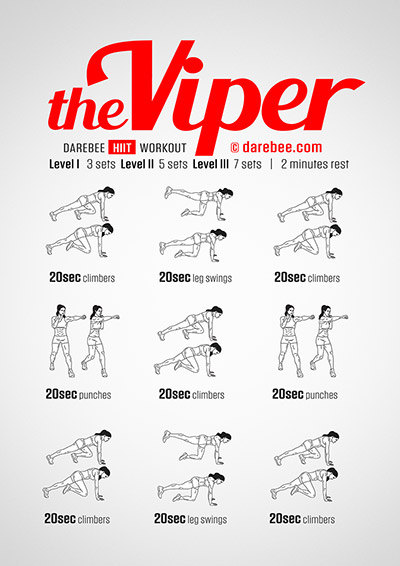

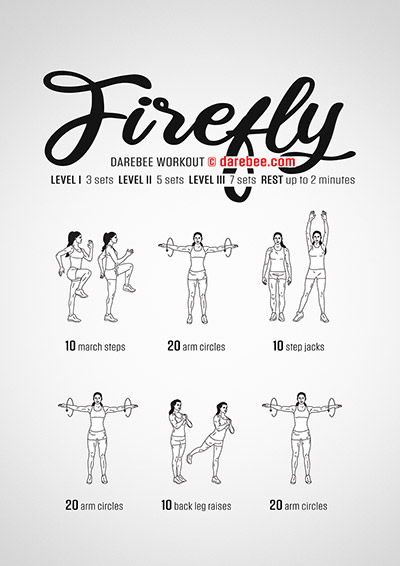

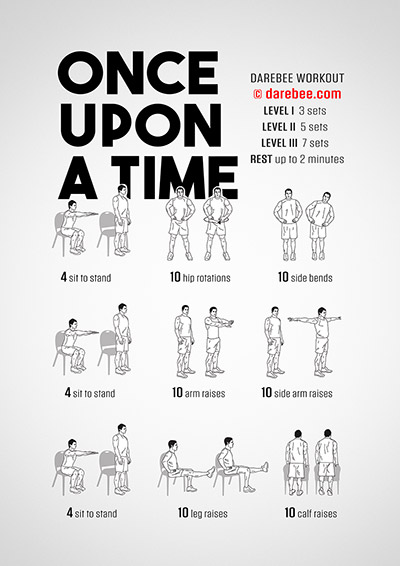

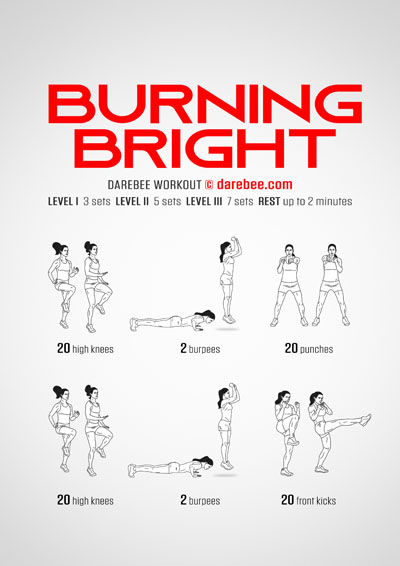

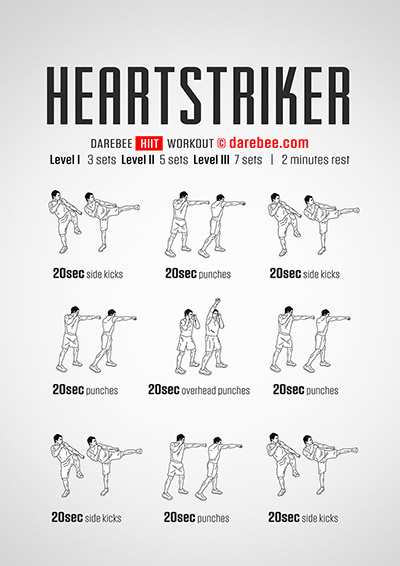

Workouts to try:

Fight-Off Cancer

Researchers at the Karolinska Institutet[4] in Sweden showed that exercise changes T-cell metabolism. T-cells are part of the immune system and develop from stem cells in the bone marrow. The Karolinska Institutet study discovered how physical exercise enhanced the ability of the immune system to fight off cancer cells. “Our research shows that exercise affects the production of several molecules and metabolites that activate cancer-fighting immune cells and thereby inhibit cancer growth,” they announced when they published the study.

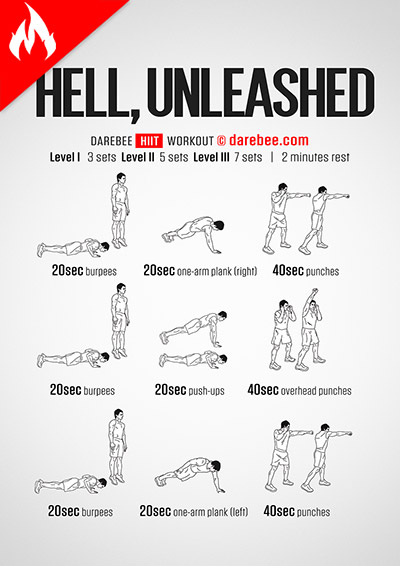

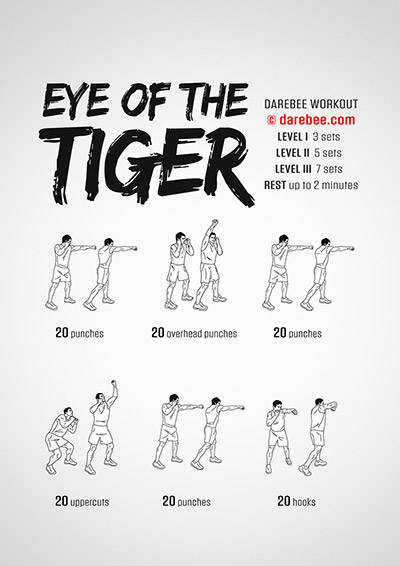

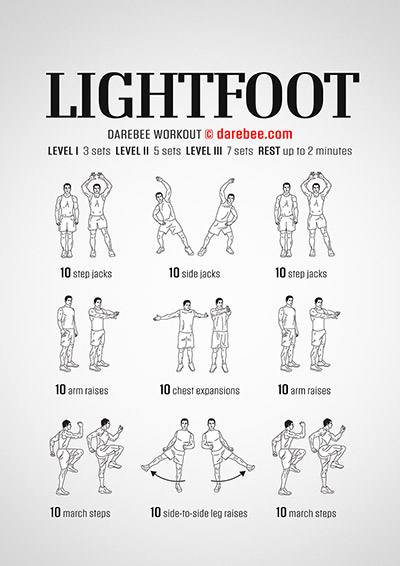

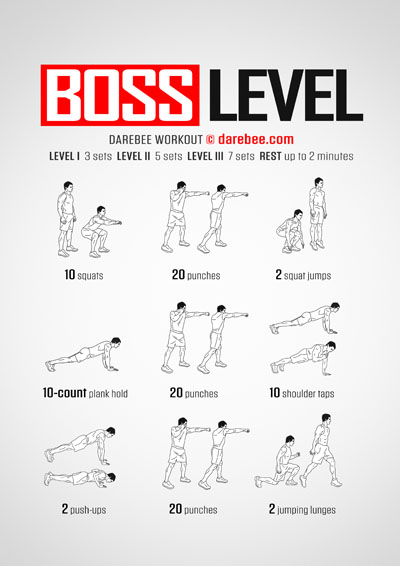

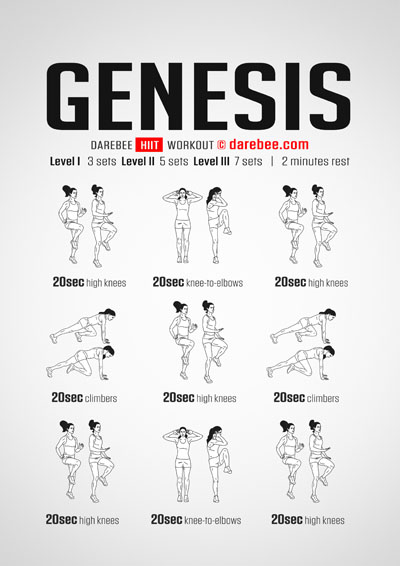

Workouts to try:

Stave-Off Dementia and Slow Down Alzheimer’s

A study of nearly 200,000 individuals[5] carried out by researchers at the University of Exeter, in the UK, found that people with a genetic disposition to dementia and Alzheimer’s could significantly reduce their chances of being affected by making lifestyle changes that include taking regular exercise.

The power of physical activity to repair the declining brain was corroborated by a further study[6] carried out by the department of Clinical Psychology of Ageing and Dementia at the University of Exeter, in the UK, which found that exercise reduces the effects of both dementia and Alzheimer’s.

The biochemical changes that happen in the body as a result of regular physical activity alter the way the body and brain operate at a cellular level and can both slow down time and reduce the effects of ageing and repair damage that has already occurred.

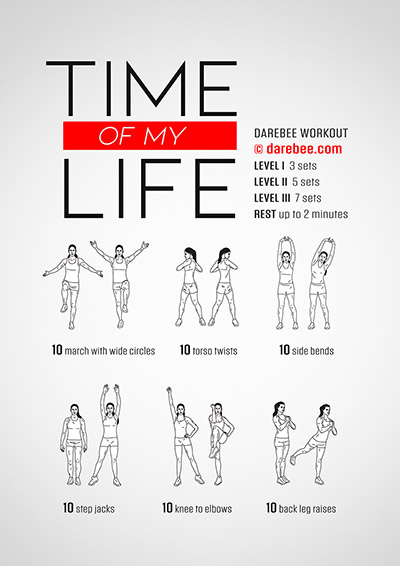

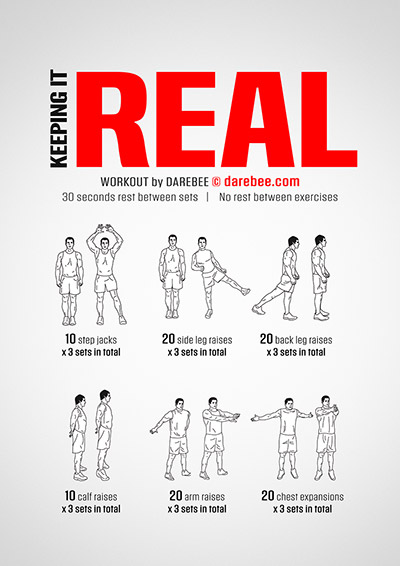

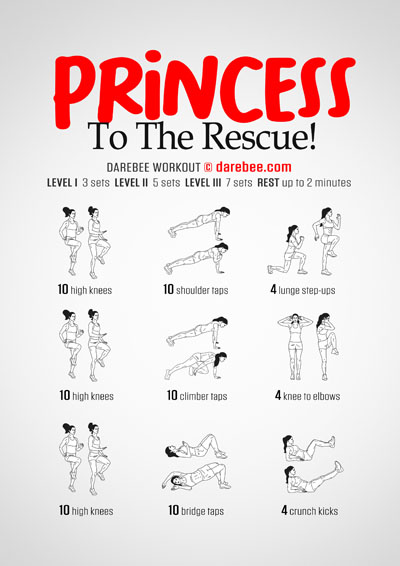

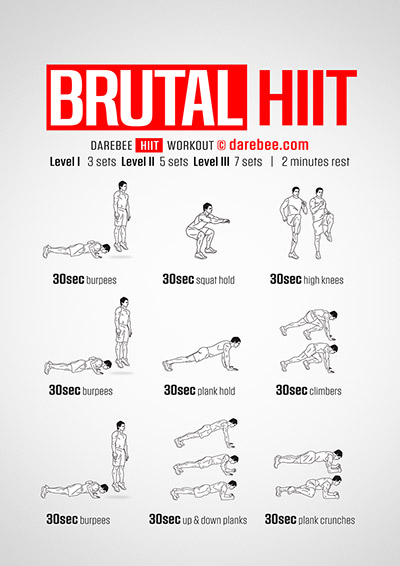

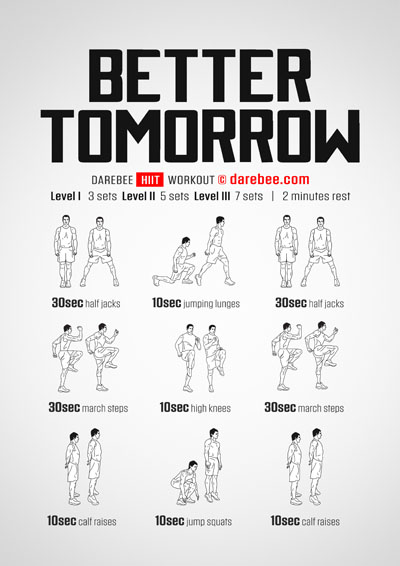

Workouts to try:

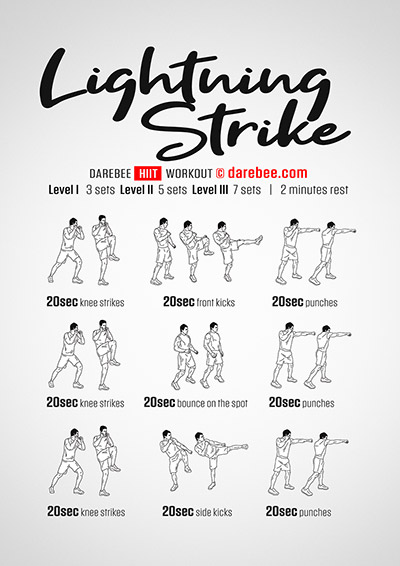

Sharpen Your Brain

We know already from other articles that go deeper into the subject that exercise based on complex combat moves sharpen the brain and actually make us smarter.

A study that used fMRI to study what happens to the structure of the brain[7] as a result of an eight week long exercise program discovered that physical activity forces the brain to undergo neural growth, known as neurogenesis, creating fresh neural connections that augment intelligence and, in the case of damage due to environmental factors or ageing, compensate for it.

Further scientific review[8] and a metanalysis of several studies conducted, on the subject, over the last decade or so back up the neurogenetic effect of exercise on the brain.

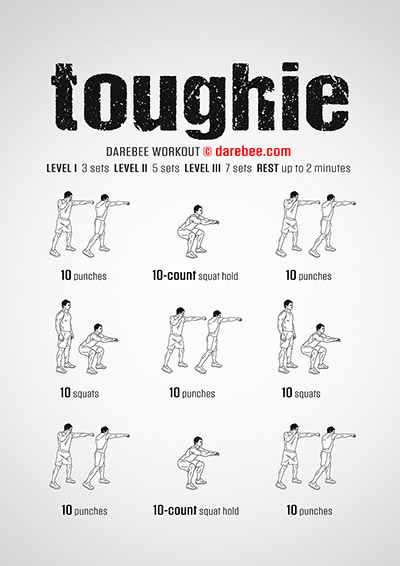

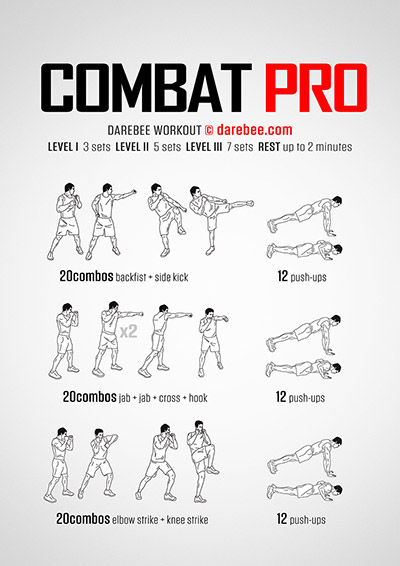

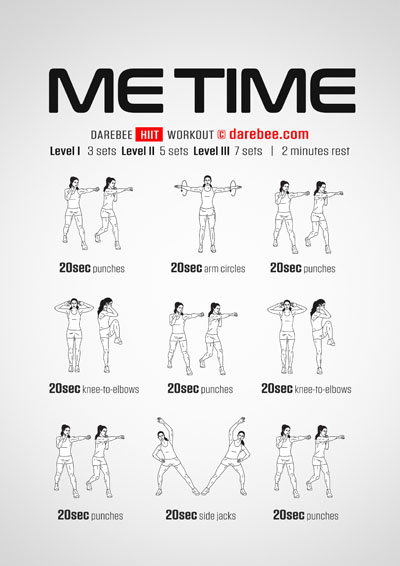

Workouts to try:

Preserve Your Vision

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is an eye disease that can get worse over time. It's the leading cause of severe, permanent vision loss in people over the age of 60. A study carried out by researchers at the University of Virginia discovered that regular exercise can both prevent and help reduce the effects of AMD.[9]

The mechanism behind this benefit is thought to be the reduction in inflammation experienced across the body as a result of regular physical activity that is fully integrated in a person’s lifestyle.

Workouts to try:

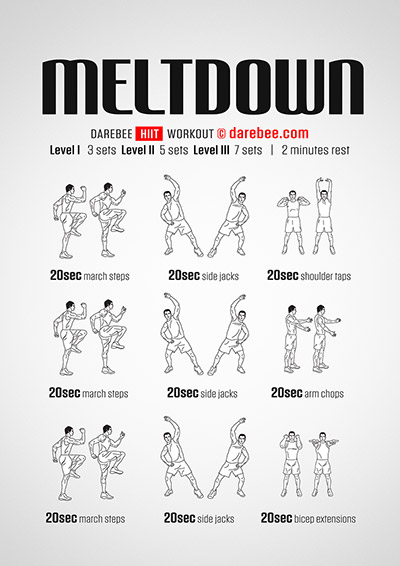

Fight-Off Anxiety

We all, at some point, feel a sense of anxiety about the future and a sense of unsettlement about our own situation in life. Even in this, however, exercise appears to live up to its cure-all reputation. Population studies[10] on behavioral disorders and the effects of non-medical external intervention factors show that regular exercise changes the endorphin production and the hormonal profile of individuals and reduces the levels of anxiety and low-grade stress that they experience.

The effects of exercise[11] on the human endocrine system and the ability of exercise to affect the production of neurotrophins (small proteins important regulators for survival, differentiation, and maintenance of nerve cells) in the brain indicate that regular exercise can prevent the development of chronic stress and anxiety and reduce the harmful mental and physiological effects that come from them.

Emotional regulation which is a key executive function that leads to better decision making and high quality outcomes is improved with exercise according to studies[12] carried out on a cross-section of adults. Even more telling, the younger we start to exercise,[13] the better off we will be in our adult years as the key structural changes in the brain that result from physical activity are laid out early on.

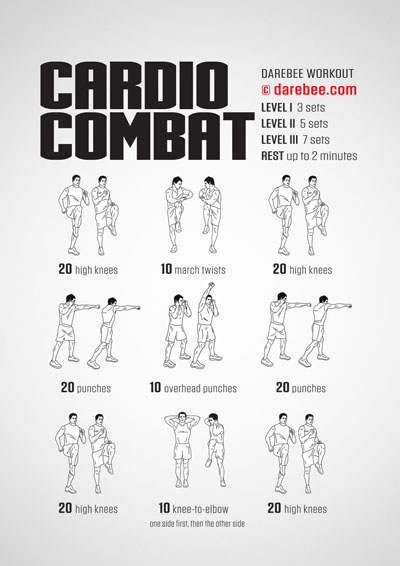

Workouts to try:

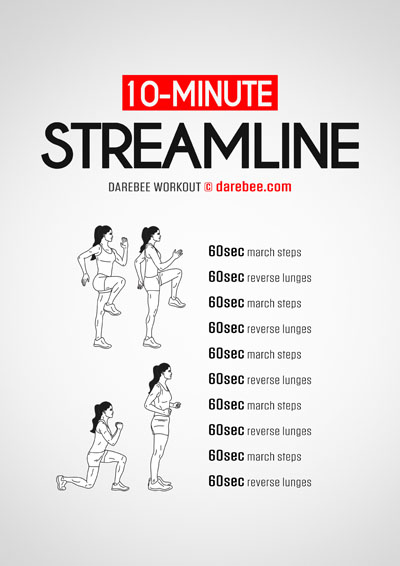

Improve Your Memory

A systematic review of 737 adults[14] who regularly took part in aerobic exercise showed that aerobic activity helps reduce degeneration of the hippocampus in the brain. This is an area of the brain that is related to memory and learning. It helps keep the brain sharper and it plays a key role in perception of facts and the judgement of specific events.

A healthier hippocampus, in general, leads to improved decision making and it affects our behavior.

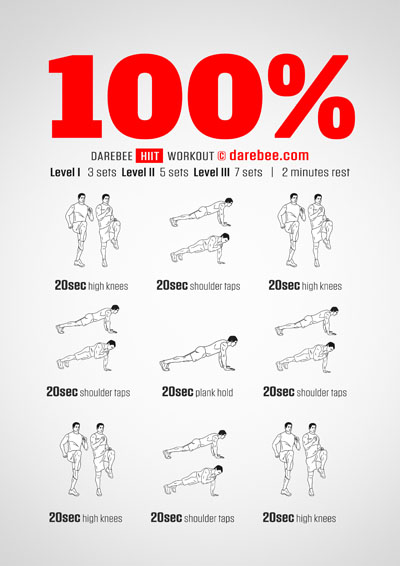

Workouts to try:

Fight-Off Covid-19

Finally, it seems that exercise also helps against Covid-19. The pandemic is still pretty new to us and data, initially, was scarce. We know that exercise in general boosts the immune system and logically it should help reduce the impact of the coronavirus on our system.

Data is now coming in. A study of 50,000 Californians[15] showed that regular physical activity plays a key role in avoiding developing severe covid-19 even if infection does take place in the first instance. A combination of mechanisms are hypothesized to be behind this resistance: improved immune system response, reduced inflammation markers in the body and improved aerobic capacity are some of the prime candidates that help protect against severe effects of Covid-19.

In another study[16] carried out amongst older adults in Europe grip strength, which is an overall indicator of strength and health, also showed a correlation between high, overall fitness in individuals and reduced hospitalizations due to Covid-19.

Workouts to try:

Summary

Regular exercise helps keep us slimmer and makes us stronger but it also has other benefits that are not so obvious which are, however, far reaching. It affects our moods, fights off depression and cancer, can help with our memory and degenerative diseases that come with old age and it improves our overall chances of survival against unexpected pathogens. By incorporating it in our life and making it part of what we do everyday, like brushing our teeth and taking a shower, we not only safeguard our health now but we also work to improve our quality of life as we age.

References

- Lieberman DE. Is Exercise Really Medicine? An Evolutionary Perspective. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2015 Jul-Aug;14(4):313-9. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000168. PMID: 26166056.

- Allen JM, Mailing LJ, Cohrs J, Salmonson C, Fryer JD, Nehra V, Hale VL, Kashyap P, White BA, Woods JA. Exercise training-induced modification of the gut microbiota persists after microbiota colonization and attenuates the response to chemically-induced colitis in gnotobiotic mice. Gut Microbes. 2018 Mar 4;9(2):115-130. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1372077. Epub 2017 Sep 22. PMID: 28862530; PMCID: PMC5989796.

- Allen JM, Mailing LJ, Niemiro GM, Moore R, Cook MD, White BA, Holscher HD, Woods JA. Exercise Alters Gut Microbiota Composition and Function in Lean and Obese Humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018 Apr;50(4):747-757. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001495. PMID: 29166320.

- Helene Rundqvist, Pedro Veliça, Laura Barbieri, Paulo A Gameiro, David Bargiela, Milos Gojkovic, Sara Mijwel, Stefan Markus Reitzner, David Wulliman, Emil Ahlstedt, Jernej Ule, Arne Östman, Randall S Johnson. Cytotoxic T-cells mediate exercise-induced reductions in tumor growth. eLife, 2020; 9 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.59996

- Lourida I, Hannon E, Littlejohns TJ, Langa KM, Hyppönen E, Kuzma E, Llewellyn DJ. Association of Lifestyle and Genetic Risk With Incidence of Dementia. JAMA. 2019 Jul 14;322(5):430–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9879. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 31302669; PMCID: PMC6628594.

- Clare, Linda & Nelis, Sharon & Quinn, Catherine & Martyr, Anthony & Henderson, Catherine & Hindle, John & Jones, Ian & Jones, Roy & Knapp, Martin & Kopelman, Michael & Morris, Robin & Pickett, James & Rusted, Jennifer & Savitch, Nada & Thom, Jeanette & Victor, Christina. (2014). Improving the experience of dementia and enhancing active life - living well with dementia: Study protocol for the IDEAL study. Health and quality of life outcomes. 12. 164. 10.1186/s12955-014-0164-6.

- Gourgouvelis J, Yielder P, Murphy B. Exercise Promotes Neuroplasticity in Both Healthy and Depressed Brains: An fMRI Pilot Study. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:8305287. doi:10.1155/2017/8305287

- Narayanasetti PTN, Thomas PT A (2017) Exercise and Neural Plasticity– A Review Study. J Neurol Neurosci. Vol. 8 No. 5:216. doi:10.21767/2171-6625.1000216

- Ryan D. Makin; Dionne Argyle; Shuichiro Hirahara; Yosuke Nagasaka; Mei Zhang; Zhen Yan; Nagaraj Kerur; Jayakrishna Ambati; Bradley D. Gelfand. Voluntary Exercise Suppresses Choroidal Neovascularization in Mice. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science May 2020, Vol.61, 52. doi:doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.5.52

- Anderson E, Shivakumar G. Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:27. Published 2013 Apr 23. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00027

- DeBoer LB, Powers MB, Utschig AC, Otto MW, Smits JA. Exploring exercise as an avenue for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):1011-1022. doi:10.1586/ern.12.73

- Zhang Y, Fu R, Sun L, Gong Y, Tang D. How Does Exercise Improve Implicit Emotion Regulation Ability: Preliminary Evidence of Mind-Body Exercise Intervention Combined With Aerobic Jogging and Mindfulness-Based Yoga. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1888. Published 2019 Aug 27. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01888

- Marcell D. Cadney, Layla Hiramatsu, Zoe Thompson, Meng Zhao, Jarren C. Kay, Jennifer M. Singleton, Ralph Lacerda de Albuquerque, Margaret P. Schmill, Wendy Saltzman, Theodore Garland, Effects of early-life exposure to Western diet and voluntary exercise on adult activity levels, exercise physiology, and associated traits in selectively bred High Runner mice, Physiology & Behavior, Volume 234, 2021, 113389, ISSN 0031-9384.

- “Effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis” by Joseph Firth, Brendon Stubbs, Davy Vancampfort, Felipe Schuch, Jim Lagopoulos, Simon Rosenbaum, and Philip B. Ward in NeuroImage. Published online November 4 2017 doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.007

- Sallis R, Young DR, Tartof SY, et al, Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. British Journal of Sports Medicine Published Online First: 13 April 2021. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104080

- Muscle strength is associated with COVID-19 hospitalization in adults 50 years of age and older. Boris Cheval, Stefan Sieber, Silvio Maltagliati, Grégoire P. Millet, Tomáš Formánek, Aïna Chalabaev, Stéphane Cullati, Matthieu P. Boisgontier. medRxiv 2021.02.02.21250909; doi: 10.1101/2021.02.02.21250909